There was a spectacular sunrise this morning. I enjoyed being up early, taking pictures of the amazing morning skies. The day was full of promise since we knew this was the long-anticipated Day Of The Giant Tortoises!

Our dinghy ride to the town of Puerto Ayora was through absolutely gorgeous, Caribbean-colored blue water. A large number of boats, ranging from ragtag and rusty to luxury yachts, were anchored in the harbor.

We had a very long walk from the entrance to the park that took us past a number of endemic Galapagos plants and trees, many of which were labeled. Gigantism is a feature of many Galapagos plants and animals. Here you can see extremely tall candelabra cactus in the background, with prickly pear (opuntia) in the right foreground.

Our first look at the giant tortoises wasn't just a look; we were able to go down into their corral with them! Sue looks worried but she's not. . . just waaaaaaay intrigued and a little in awe to be so close to something neither of us ever thought we'd experience personally!

One of the most significant aspects of life in the Galapagos Islands is that the land animals are predominantly reptiles. In most of the rest of the world, mammals are predominant. So this encounter with tortoises was important for a number of reasons.

When the islands were first discovered, it is estimated that there were as many as 300,000 tortoises. They were everywhere, and the word "Galapagos" reflects the old Spanish word for saddle, referring to the saddle-looking shell of the tortoise. Humans and natural forces reduced the numbers to 15,000--not yet an endangered species, but a frightening decrease in populations once so robust. The introduced goats, pigs, and other predators (they eat the tortoises' eggs) and competitors of the tortoises have been eradicated on many of the islands, which helps a great deal with the tortoise population.

Whalers and buccaneers captured tortoises and brought them aboard their ships because they can live for three to six months without food or water. When turned on their backs, the tortoises were immobile until slaughtered for fresh meat at sea.

This is a group of smaller males. You can see the differentiation between them; their shells (also called a carapace) have slightly different shapes.

The saddleback subspecies (the one whose head is sticking out the most) gain their name from the front part of the shell that rises up above the head to give the appearance of a saddle. These subspecies inhabit dry barren islands where their only food is cacti. They need to stretch up their heads and necks to reach this food source, so the saddle shape allows for this. This adaptation is an evidence of natural selection, a process which God ordained to allow organisms to be fruitful and multiply in new environments.

The dome subspecies (such as the first one on the left) inhabit more fertile islands with plenty of grass and low lying shrubs, therefore they don't need the raised front shell.

The third kind of carapace is intermediate between the other two. Each tortoise is from a different island.

When Darwin visited the Galapagos in 1835, the Vice Governor told him that he could tell which island a tortoise was from by the shape of his shell, and Darwin didn't believe him. He was wrong on THAT, too.

When we visited a corral with all female tortoises from various islands, SOMEBODY in our group suggested that we get a picture of "the girls and the girls." (Hint: She's wearing a green Probe shirt and smiling at the camera.)

The ladies weren't concerned about the tortoises running away. As Darwin wrote,

"The inhabitants from observing marked individuals, consider that they travel a distance of about eight miles in two or three days. One large tortoise, which I watched, walked at a rate of sixty yards in ten minutes, that is 360 yards in the hour, or four miles a day."

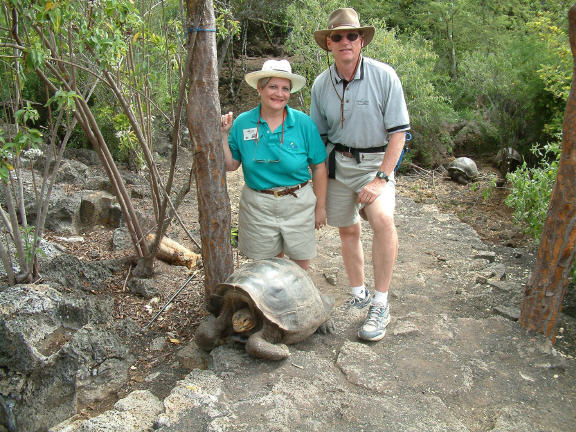

This was a moment that we will remember forever: posing together for a picture with a giant tortoise.

One corral features Lonesome George, which is the lone survivor of the subspecies from Pinta Island. Attempts to breed him with closely related females from other islands have so far failed. Some young students, peering at George, asked why they don't just clone him. It seems like such a reasonable idea, right? But first of all, cloning isn't that easy, and secondly, we'd still end up with another male and no female.

Note the saddleback shell from this rear view.

Darwin tried an experiment with the tortoises that would get him thrown in jail if he did it today. He recorded in The Voyage of the Beagle:

"For some time after a visit to the springs, their urinary bladders are distended with fluid, which is said to gradually decrease in volume, and to become less pure. The inhabitants, when walking in the lower district, and overcome with thirst, often take advantage of this circumstance, and drink the contents of the bladder if full: in one I saw killed, the fluid was quite limpid, and had only a slightly bitter taste."